Circadian rhythm

Discover why some people jump out of bed in the morning while others struggle to get up every day.

There are people who seem to jump out of bed in the morning, and there are those who struggle with waking up every day. How come?

Every person has their own circadian rhythm. The rhythms of people vary in two dimensions: one is the period in which it cycles, which for healthy adults is 24:18h +/- 12 minutes. [1] The other is the time to which the clock is set, scientifically called the circadian phase. The three main factors—genetics, age, and environment—determine the time of your internal clock. By shaping your environment accordingly, you can actively influence this.

Genetic Predisposition

In 2017, the Nobel Prize for Medicine was awarded to three researchers for their discoveries of the molecular mechanisms controlling the circadian rhythm. [2] It involves an oscillating gene expression throughout the day into certain proteins and their degradation overnight, which manifests in the circadian rhythm we observe. [3]

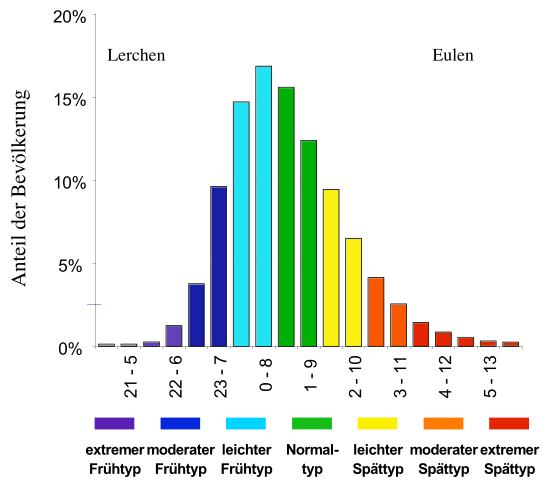

Approximately 40% of the population tends to wake up earlier (“larks”), while about 30% would naturally wake up later (“owls”). [4] The tendencies for morningness, medium type, or eveningness are distributed in an almost Gaussian curve.

Distribution of larks and owls, showing that moderately early chronotypes prevail.

Age

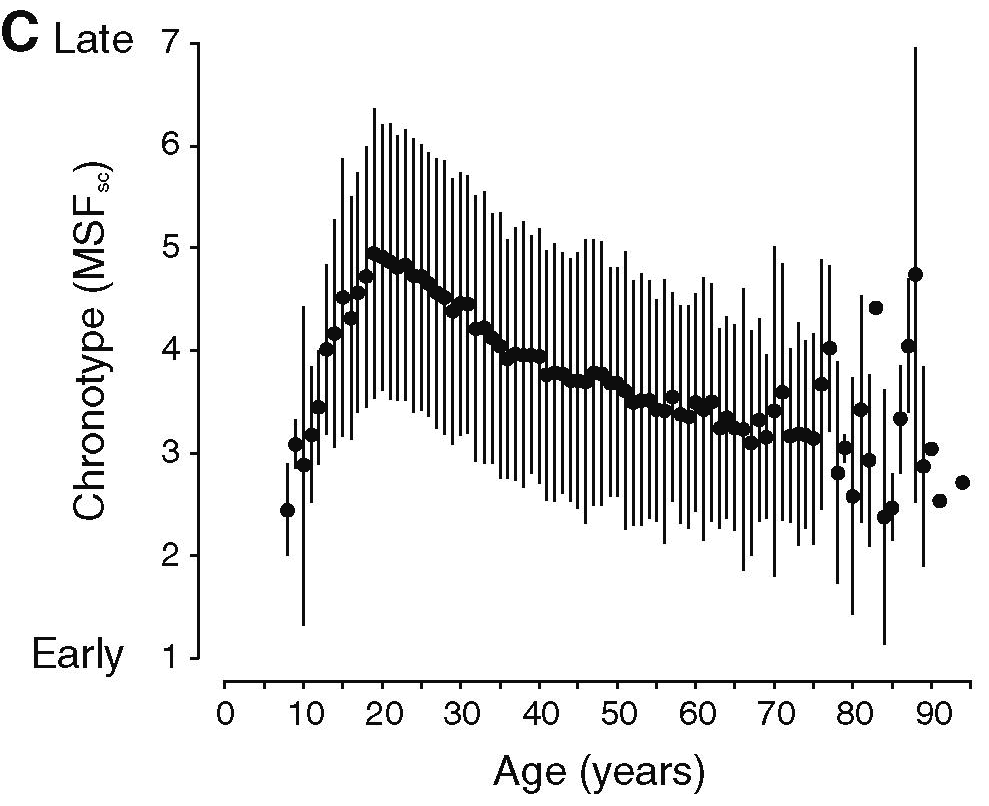

The circadian rhythm changes with age. In adolescence, it experiences a peak delay of 1-3 hours, which leads teenagers and young adults to typically be late risers. [5] As one ages, the circadian clock advances, which is why many older individuals wake up early in the morning. [6] Furthermore, the circadian rhythm dampens overall with age. Therefore, a rhythmic lifestyle (e.g., regular meal times or light exposure times) can be very beneficial for the well-being of older adults. [7]

Centre of sleep on days off (MSF, used as an approximation for chronotype) over age. From [11].

External Time Cues

To avoid drifting away from the actual time of day, your circadian clock synchronizes to various stimuli that serve as indicators of the time of day. These stimuli, scientifically called time cues (after which this website is named), cause your internal clock to delay or advance depending on the timing of the stimulus. [4] Light is considered the most important time cue, but other stimuli such as food intake or physical activity can also affect your internal clock. [8,9,10]

If you know how various time cues influence your circadian rhythm, you can design your lifestyle so that your internal clock aligns with your external schedule.